Most people assume creativity belongs only to experts. But a silent category exists between amateurs and full-fledged professionals—the borderline professionals. These are individuals who have the desire to create, and just enough basic skill to understand what they want, yet they struggle to execute.

Today, AI changes that equation.

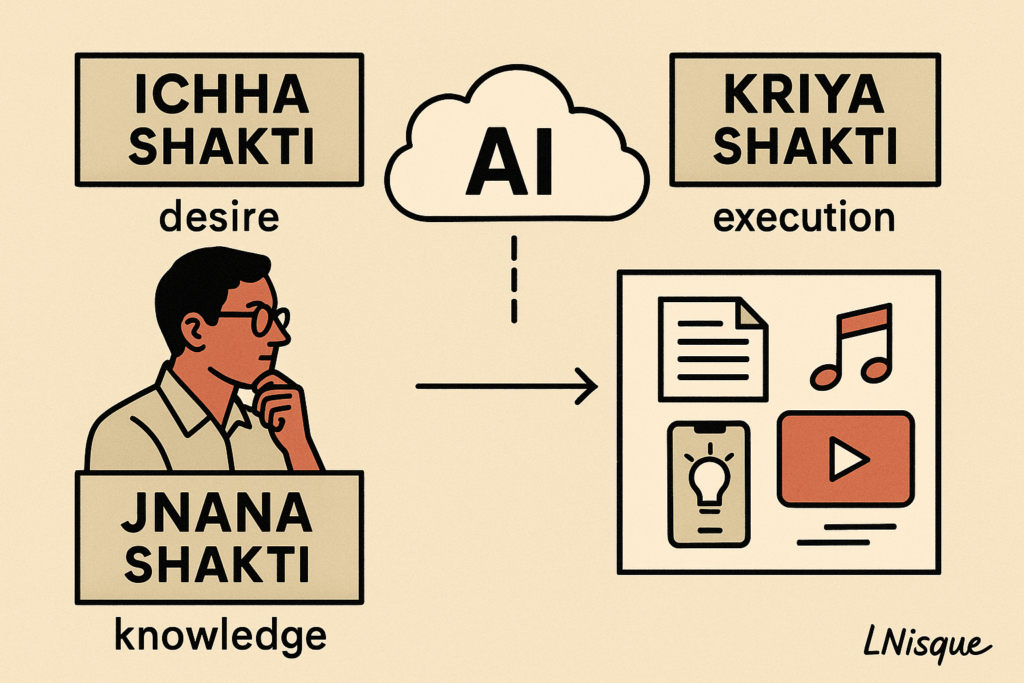

The Ancient Framework That Explains Modern AI

In the Lalita Sahasranama, creation is rooted in three forces:

- Ichha Shakti — the deep desire or will

- Jnana Shakti — the knowledge or understanding

- Kriya Shakti — the power to execute

In my book Directing Business, I highlighted how these three powers capture the entire arc of creation. Most people possess the first, many have some version of the second, but very few have the third.

This is where AI steps in—not as a replacement for human skill, but as the missing Kriya Shakti that unlocks execution.

Who Are Borderline Professionals?

Borderline professionals are not amateurs. They are not novices. They are people who:

- Have a genuine desire to create

- Possess basic foundational knowledge

- Can articulate what they want

- But get stuck when it’s time to execute

They often sit on ideas for years—songs they wanted to compose, books they wanted to write, companies they wanted to start, designs they always imagined but never completed.

Their limitation is almost always Kriya Shakti—the ability to translate intent and knowledge into a finished creation.

AI Completes the Creation Triangle

If you possess:

- Ichha (desire)

- Jnana (basic understanding)

AI now gives you:

- Kriya (execution superpower)

This shifts the creative world in a fundamental way. AI does not magically inject expertise into you.

Instead, it amplifies your minimum viable expertise.

In other words:

If you can imagine it and understand it at a basic level, AI can help you build it.

Real Examples of Borderline Creators Becoming Real Creators

1. Writing & Storytelling

People who always wanted to write but struggled with structure or flow can now produce full essays, chapters, and scripts. AI becomes the co-author that takes their intent and shapes it into polished work.

2. Music & Composition

A person who can hum a tune or grasp rhythm but lacks musical training can now generate full compositions, lyrics, and studio-quality tracks.

3. Entrepreneurship

Someone with a startup idea but no experience in planning, pitching, or prototyping can now generate:

- business plans

- branding

- pitch decks

- landing pages

- even early product mockups

In short, AI provides the scaffolding for company creation.

4. Multimodal Creativity

Text → Images → Video → Audio → Apps

With modern multimodal AI, the entire pipeline of creativity becomes accessible—even if the individual has never been trained formally.

The Big Insight: Skill Is Not Dead—It Is Amplified

You still need some Jnana Shakti—some grasp of your domain. AI cannot replace absolute ignorance.

But the amount of knowledge needed to start has dramatically dropped.

Earlier, you needed 100% skill to get 100% output.

Now, even with 20–30% knowledge, AI multiplies your ability to produce a finished work.

This is the true empowerment.

Why This Is the Best Time for Borderline Professionals

For the first time in history:

- You don’t need a studio to compose.

- You don’t need a publisher to write.

- You don’t need a team to launch a startup.

- You don’t need a design degree to create visuals.

- You don’t need a production crew to make videos.

If you have deep desire (Ichha) and basic understanding (Jnana), AI gives you Kriya at a never-before scale.

This makes today the most powerful era for borderline professionals—those who were always “almost there,” waiting for a catalyst.

Conclusion

Creativity no longer belongs only to the trained elite. It belongs to anyone with the will to create and the willingness to learn just enough to guide AI.

AI completes the Ichha–Jnana–Kriya triad.

It transforms borderline professionals from dreamers into doers, and from doers into creators.

The door is open wider than ever.

And if you’ve always stood just outside it—this is your moment to walk through.

Infographic based on this article (using Nana Banana Pro)